by Maya Chari

APM Research Lab Ten Across Data Journalism Fellow

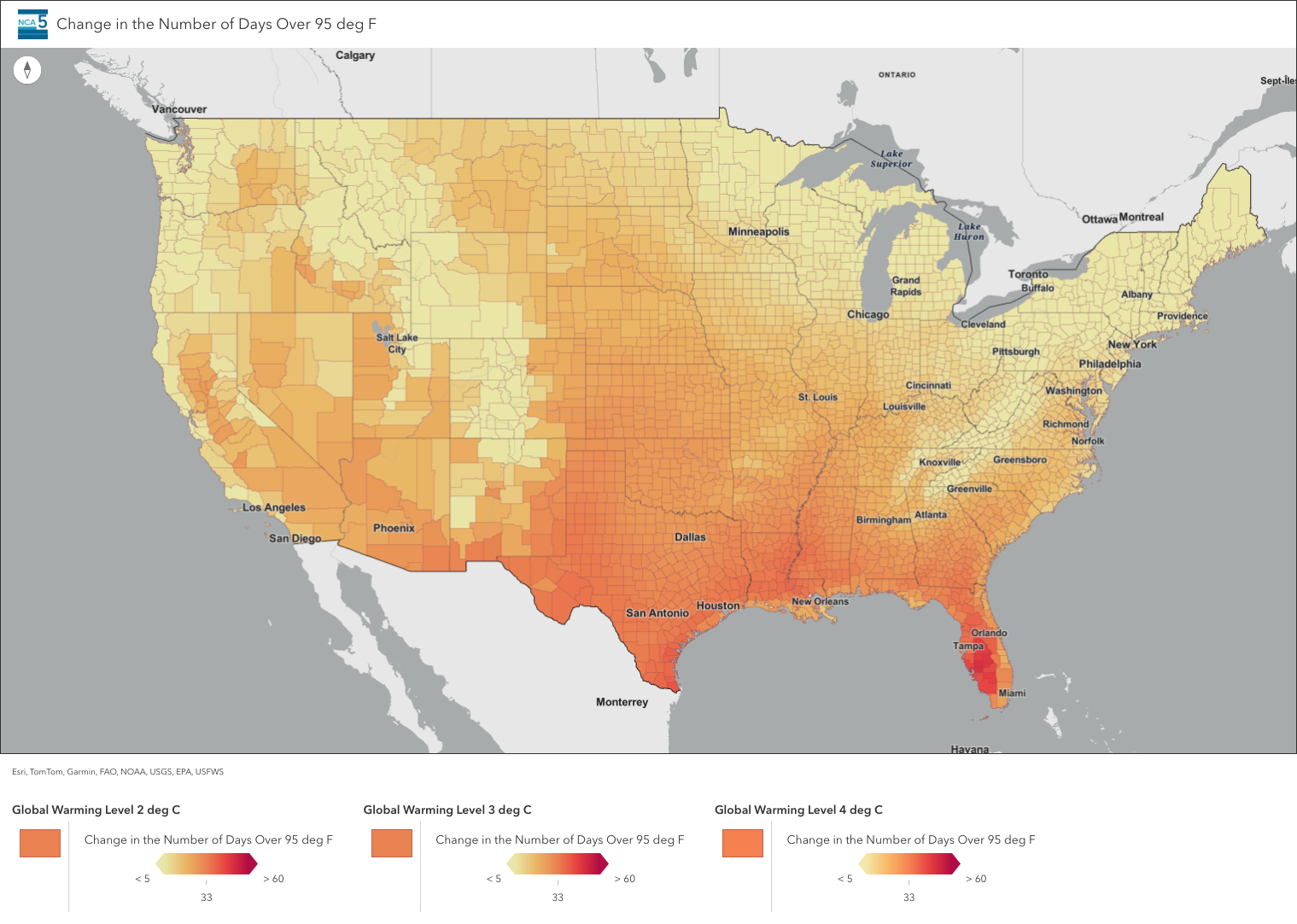

Scientists agree that the world is warming. Heat waves now occur twice as frequently as they did in the 1980s, and the length of heatwave season has tripled in the last sixty years. These trends are forecast to continue.

The southernmost portion of the U.S., where hot weather has always been part of life, now finds itself on the front lines of more dangerous conditions. Rapid growth in “Sun Belt” cities in the later 20th century brought with it concrete sprawl, creating urban heat islands that exacerbate warming. Intensifying extreme heat conditions pose an array of risks to public health, including rising rates of heart attacks, respiratory conditions, suicide and violence.

This region’s natural familiarity with ordinary heat has combined with the new urgency of extreme heat emergencies to produce forward-looking models of heat mitigation practices. A dozen cities along the Interstate 10 corridor, including Phoenix, Tucson, Jacksonville, El Paso and San Antonio, have offices dedicated to improved sustainability and resilience, and the nation’s first dedicated state and municipal chief heat officers are in California, Arizona and Florida.

California and Arizona were also two of the first to create state-level heat action plans to address the public health and economic effects of extreme heat. According to Grace Wickerson, the Senior Manager for Climate and Health at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), Arizona’s plan is especially robust and could serve as a model for other states. However, recent federal funding cuts have slowed wider progress.

The FAS Climate and Health Initiative develops science-based policy recommendations to help governments prepare for extreme heat. Over the past year, FAS has documented extensive cuts and freezes to federal funding for heat relief grants. Multiple grants intended to subsidize cooling and energy costs for low-income households have been frozen, discontinued, or subject to staff layoffs. Grant funds to help communities prepare for heat emergencies before they happen have also been frozen or slashed.

Wickerson said that in response, FAS policy recommendations moved away from federal-level support and toward what can be managed more independently at the local and state level. Even in the absence of federal funding, they said, progress is possible through strategic choices, like changes to permitting and zoning law.

Douglas Melnick, the assistant director of the Department of Resilience and Sustainability in San Antonio, Texas, said that his city has been adopting cooling initiatives out of necessity for more than a decade.

“When I first got here, the city wasn’t really working in the climate space. I remember talking to stakeholders and city leaders. I showed them climate projections and the response was, oh, it’s always [been] hot,” he said.

That’s changed as temperatures have risen further. “It’s gotten to the point where you do not leave the house [during the summer]” he said. “It’s oppressive. It’s awful, and it’s not sustainable. There’s still people who underestimate the level of threat that we face with heat to public health, as well as every summer, you just wait for the grid to collapse. It’s going to happen. We’re talking about weeks of 100+ degree temperatures. The grid can’t sustain that.”

According to Melnick, San Antonio’s sustainability office aspires to devise comprehensive plans for known catastrophic heat-related risks, like a summertime power outage. Over the past twelve years, the sustainability office has implemented initiatives like the Cool Neighborhoods Program, mapping the most heat-vulnerable neighborhoods in San Antonio. In this city, like its neighbors along the I-10, lower-income neighborhoods tend to have less shade, resulting in higher temperatures and greater vulnerability to extreme heat.

San Antonio has piloted a series of programs to address extreme heat by providing lower-income residents with cool, reflective roofs and weatherization assistance, installing cool pavement, monitoring temperature and air quality in neighborhoods across the city, and working with the transit office to establish temperature-controlled transit stations.

Melnick said San Antonio has not relied directly on federal funding for any of these programs. However, cuts to funding for other departments have left the city with a tighter budget overall, and discretionary programs like heat relief are often the first to go when sacrifices must be made.

“Right now, we’re just trying to cobble together funding for these programs from existing city resources, and it only goes so far,” Melnick said. “We don’t see these programs going away, but the plan was always to do proof of concept and then scale across the city, and without resources, that’s not going to happen.”

Melnick said that San Antonio is also seeking out philanthropy, nonprofits, and community foundations to fill in the gaps in funding, and he suspects that other cities are doing the same. The city has partnered with Climate Ready Communities, a nonprofit that provides plans and resources to local governments to help them address climate challenges with limited financial resources. They’re also partnering with local businesses to see if they will serve as locations for residents to keep cool.

“Unfortunately, what we’ve heard is that there’s so much uncertainty that even businesses and foundations are pulling back on their work,” he said. “It’s a really difficult time right now.”